Welcome to the first installment of our MEL Blog Series. Learn more about a foundation’s approach to strategic learning in our second post and stay tuned for the final installment on using qualitative data to communicate effectively.

Monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) must go beyond bean counting to create sustainable impact. Too often standard data collection summarizes activities but fails to determine whether and why outcomes are achieved. Findings are summarized in lengthy reports that rarely reach audiences outside the project. These challenges—output instead of outcomes-focused metrics and limited translation of learning into action—cut across the environment, development, and similar sectors. So how can organizations design MEL to inform decision–making?

Start with Asking the Right Questions

Our experience shows us that grounding programs in a learning framework enables clients to go beyond static standard reporting. Strong learning frameworks provide structure to the data collection and sharing process, linking indicators and outcomes to the theory of change to capture program achievements.

When working with clients to develop learning frameworks, we ask:

- How will you achieve the desired program outcome? Begin by articulating a clear theory of change that outlines how each activity will lead to the desired outcome, including each step along the way.

- What are the underlying assumptions in the proposed theory of change? After creating a theory of change, identify and test the assumptions underlying the proposed process.

- What is beyond your control? Consider questioning beyond the manageable interest of your program to demonstrate how the activities may move the field toward intended outcomes.

Learning Frameworks in Practice

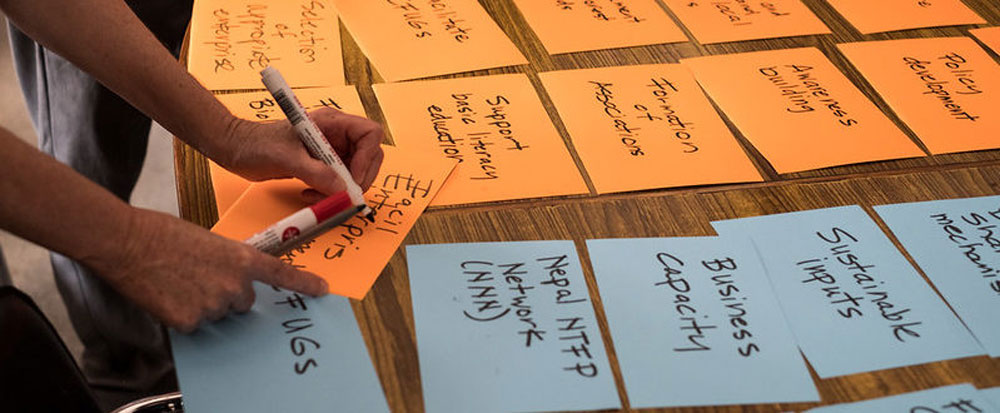

Facilitating evidenced–based learning is central to our work on USAID’s Measuring Impact II (MI2) project. Along with our partners Foundations of Success and ICF, we used these three questions to cocreate a learning framework with USAID’s Conservation Enterprises Collaborative Learning Group, a cross-mission initiative formed to strengthen the evidence base and share learnings around conservation enterprises (CEs).

How will you achieve the desired project outcome?

First, we adapted the Open Standards for the Conservation of Nature (CS) to visualize the step-by-step impacts of each CE activity that would lead to the desired project outcome: improved biodiversity conservation. With the CE Collaborative Learning Group, we facilitated the creation of a high-level theory of change (pictured below). The theory posits that if stakeholders gain benefits, such as increased incomes from CEs, then they will be motivated and enabled to change behaviors. By outlining these steps, we created a shared learning framework to help separate teams track progress toward biodiversity conversation.

What are the underlying assumptions in the proposed theory of change?

After mapping this step-by-step process, we identified and tracked the assumptions inherent to the theory of change. Through the CE Collaborative Learning Group, we produced the CE Learning Agenda, which outlines these assumptions as learning questions to determine if the approach and enabling conditions will support the desired outcomes.

We also developed indicators to monitor the assumptions. For example, tracking the benefits participants accrued from CEs simply tells us if benefits are received (step 2). However, tracking whether participants perceive the distribution of benefits as fair tests the assumption that receiving those benefits causes the desired behavior change.

What is beyond our control?

Finally, we encouraged the CE Collaborative Learning Group to look beyond what is in their immediate control and toward the desired outcome: increased biodiversity conservation. If activities only measure the cash generated by a conservation enterprise (mostly in their control), they may miss contextual changes that could impact the assumptions underlying the theory of change. For example, if the activity also tracks regional habitat destruction, it may become clear that enterprises are generating cash, but the destruction remains unchanged because new actors have arrived in the area. Knowing these details enables teams to consider if they can reach the new actors, or if they need to adapt their approach to address what is currently out of their manageable interest. In these circumstances, strong MEL systems can inform opportunities for Thinking and Working Politically.

Systems for Ongoing Learning

Asking informative questions is at the heart of all monitoring, evaluation, and learning programs. Through our work on MI2, we’ve seen that creating strong learning frameworks can take those questions from output–focused bean counting to effective shared learning for decision making.